,

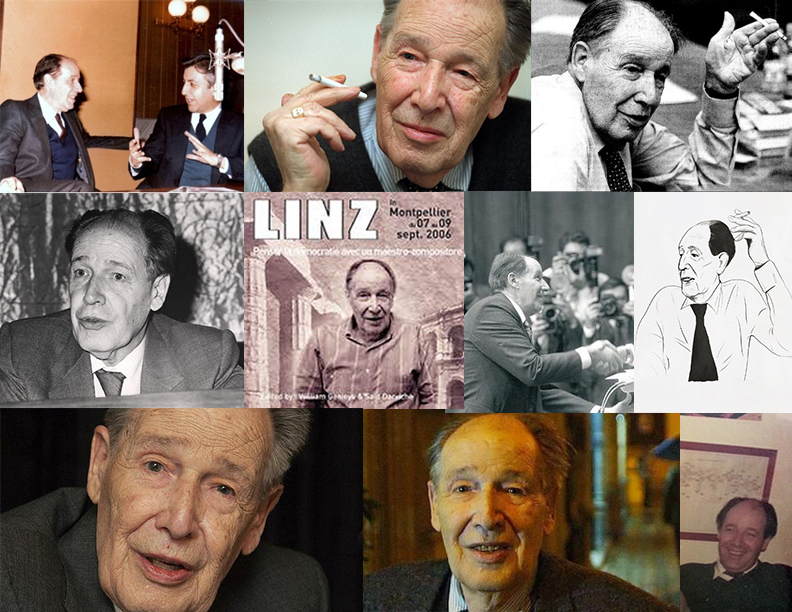

Juan Linz is Sterling Professor Emeritus of Social and Political Science at Yale University, where he holds appointments in the departments of sociology and political science. He is famous for his work comparing styles of authoritarian and totalitarian governance, and, since the Cold War, his argument in pieces like "The Perils of Presidentialism" that presidential democracies are inherently less stable than their parliamentary peers, and particularly prone to devolve into dictatorships. The United States has long been the exception to that pattern, but with a new debt or budget crisis every few months, that could be changing. I spoke to Linz on Friday; a lightly edited transcript follows.

Dylan Matthews: When you wrote "The Perils of Presidentialism," the United States was the exception to the rule. But do you think your critique of presidential systems is starting to apply here as well?

Juan Linz: What I say in my essay is applicable to the United States. I initially thought the United States was escaping the problem, because of the lack of discipline in the parties, and the relatively good relationships among the legislators. Obviously things have been changing, but I think there are some structural factors that make it particularly dangerous in the United States. Most notable are the midterm elections, which divide the presidential mandate into two periods.

Furthermore, I think there have been some changes in the parties. The degree to which the coattails of the presidents carry the party are more limited, and the influence of the president on the congressional party is more limited. It is more dependent on outside grassroots than on the internal working of the legislature. All the Washington bashing says "the problem is Washington." That is not very helpful in solving problems with legislators.

The structural problems are not the ones I propose in my book. Initially it was much less severe. When I published my book ["The Failure of Presidential Democracy"] in Spain, the cover there was the White House and I said I’d prefer some other presidential palace. But now it's failed the same way.

I don't think any of the constitutional aspects can be changed. You see the electoral college and the overrepresentation in the Senate of less populated states, all of that makes it a constitutional matter, and makes political reforms much more difficult.

DM: Do you think sub-constitutional features of the American system, like the filibuster, are contributing to the problem?

JL: Obviously. The president, and the funny thing is that in America, and in presidential systems in general, people expect the president to govern, but the president in fact has a limited power to govern. He has to get his team together in many aspects of policy. He comes immediately, very soon to campaign in the Congressional midterms. If he doesn’t win, he risks losing support in the House. And then comes the second term, where he begins to be something of a lame duck. And at the end there's a year-long process of primaries and competition for becoming the next president. The timing you have to really effectively govern is very limited.

He cannot delegate more responsibilities on the cabinet members. There was an article I saw about making the cabinet more important, but that is also difficult. It is not a coalition, a party coalition as in Europe or parliamentary system, where the cabinet is from the ruling coalition in the legislature.

In the U.S., everything used to be easy, so that it could afford to deal with some misgovernment, to some extent. I don’t see it being that easy to reform. If you cut down on some of the enormous electioneering maybe, along with this stupid idea of demanding a commitment of legislators when they don’t know what they’ll do in the future. It’s like we’re in Poland of the 18th century, when the legislators were dependent on the commitments they made and not the needs of the party.

I wish there were more responsible government, people deciding what they'll do after they’re elected. I think that the idea that a leader commits himself to the voters and he does what they say is, in principle it sounds good, but it becomes very dysfunctional at times.

DM: Most other presidential systems have collapsed into dictatorships at one point or another. If you had to hazard a guess, do you think that's in our future?

JL: I don’t know. I think there’s still enough political wisdom in this country to avoid it, but obviously in many countries in Latin America and other parts of the world a crisis like the debt ceiling would easily lead to a military coup. Look at the enormous amount of effort to renominate President Chavez in Venezuela. So in some ways authoritarian solutions, or giving exceptional powers to the president, are one way of solving these problems, but they’re not a very healthy one either.

DM: When one touts parliamentarism in the United States, the response is often, "Well Europe has parliaments, see how well they're doing!" Is there any truth to that?

JL: The level of general welfare for everybody there, the health statistics and stuff like that, is much better than the U.S. In, for example, the UK, there's considerably more equality of opportunity and better living standards and public services for the population as a whole. I think that the European welfare state has been reduced or stopped somewhat in its course but is there still for everybody, and will be there. I think that’s the fundamental difference between the U.S. and Europe. In that sense I don’t think they’re doing that badly.

DM: You're pessimistic about serious reforms to the U.S. system, but are there some smaller bore reforms you could see happening?

JL: Certainly for blockage of decision-making, I think one of a few things may happen. Some form of proportional representation in the electoral college, for some states at least, could happen. But, for instance, the equality in the Senate will obviously not be changed. That’s from the Founding Fathers. That’s a compromise to make the states possible. There are certain things that are very difficult to change since you need almost unanimity. And sometimes you need to do things without unanimity.

The Perils of Presidentialism

By Juan J. Linz

As more of the world's nations turn to democracy, interest in alternative constitutional forms and arrangements has expanded well beyond academic circles. In countries as dissimilar as Chile, South Korea, Brazil, Turkey, and Argentina, policymakers and constitutional experts have vigorously debated the relative merits of different types of democratic regimes. Some countries, like Sri Lanka, have switched from parliamentary to presidential constitutions. On the other hand, Latin Americans in particular have found themselves greatly impressed by the successful transition from authoritarianism to democracy that occurred in the 1970s in Spain, a transition to which the parliamentary form of government chosen by that country greatly contributed.

Nor is the Spanish case the only one in which parliamentarism has given evidence of its worth. Indeed, the vast majority of the stable democracies in the world today are parliamentary regimes, where executive power is generated by legislative majorities and depends on such majorities for survival.

By contrast, the only presidential democracy with a long history of [End Page 51] constitutional continuity is the United States. The constitutions of Finland and France are hybrids rather than true presidential systems, and in the case of the French Fifth Republic, the jury is still out. Aside from the United States, only Chile has managed a century and a half of relatively undisturbed constitutional continuity under presidential government-but Chilean democracy broke down in the 1970s.

Parliamentary regimes, of course, can also be unstable, especially under conditions of bitter ethnic conflict, as recent African history attests. Yet the experiences of India and of some English-speaking countries in the Caribbean show that even in greatly divided societies, periodic parliamentary crises need not turn into full-blown regime crises and that the ousting of a prime minister and cabinet need not spell the end of democracy itself.

The burden of this essay is that the superior historical performance of parliamentary democracies is no accident. A careful comparison of parliamentarism as such with presidentialism as such leads to the conclusion that, on balance, the former is more conducive to stable democracy than the latter. This conclusion applies especially to nations with deep political cleavages and numerous political parties; for such countries, parliamentarism generally offers a better hope of preserving democracy.

Parliamentary vs. Presidential Systems

A parliamentary regime in the strict sense is one in which the only democratically legitimate institution is parliament; in such a regime, the government's authority is completely dependent upon parliamentary confidence. Although the growing personalization of party leadership in some parliamentary regimes has made prime ministers seem more and more like presidents, it remains true that barring dissolution of parliament and a call for new elections, premiers cannot appeal directly to the people over the heads of their representatives. Parliamentary systems may include presidents who are elected by direct popular vote, but they usually lack the ability to compete seriously for power with the prime minister.

In presidential systems an executive with considerable constitutional powers-generally including full control of the composition of the cabinet and administration-is directly elected by the people for a fixed term and is independent of parliamentary votes of confidence. He is not only the holder of executive power but also the symbolic head of state and can be removed between elections only by the drastic step of impeachment. In practice, as the history of the United States shows, presidential systems may be more or less dependent on the cooperation of the legislature; the balance between executive and legislative power in such systems can thus vary considerably. [End Page 52]

Two things about presidential government stand out. The first is the president's strong claim to democratic, even plebiscitarian, legitimacy; the second is his fixed term in office. Both of these statements stand in need of qualification. Some presidents gain office with a smaller proportion of the popular vote than many premiers who head minority cabinets, although voters may see the latter as more weakly legitimated. To mention just one example, Salvador Allende's election as president of Chile in 197-he had a 36.2-percent plurality obtained by a heterogeneous coalition-certainly put him in a position very...